Behind the paper: Real time, portable sequencing for Ebola surveillance

03 Feb 2016Hurrah, our paper describing the Ebola sequencing surveillance work is out today (ReadCube Link)!

I previously blogged about it here.

This work monopolised nearly all of mine and Josh’s time in 2015, leaving in our wake a raft of unfinished projects, unanswered emails and frustrated collaborators (sorry, I promise we’ll get back to your stuff soon!).

There has been some nice press coverage today. The original announcement was on this blog, and it was previously beautifully covered by Ed Yong.

Coverage:

I thought it might be nice to do a little “behind the paper” post as this project has had more crazy stuff going on behind the scenes than many.

Prelude

One of the inspirations and motivations for this project was an editorial from Pardis Sabeti and colleagues in Nature. They noted that during the West African Ebola epidemic, there was an extraordinary gap between numbers of available genome sequences and the numbers on the epidemic curve, with no single genome sequence having been released between 2nd August and 9 November, a period when there was conservatively >15,000 cases of Ebola. This was shocking to me and them.

There were of course many reasons for this; some were different to work around, for example the time and difficulty taken to ship and analyse samples in remote laboratories, often located in US and Europe. Other excuses were less justifiable - such as locking up sequences waiting for formal articles to be published.

Of course for those who know about our labs work it was no big mental jump for us - or you - to realise that sequencing done in situ would be better. And of course by this time we were knee-deep in MinION sequencing work. It seemed obvious to us that Ebola sequencing could be done on nanopore near the portable diagnostic laboratories set up across West Africa. But first we had to try it out.

Part 1: The big setup

Josh works for an NIHR funded project called the Surgical Reconstruction and Microbiology Research Centre (SRMRC) which has strong links to the military through their trauma research. Through this connection we were able to get in contact with some military medics including Matt O’Shea, Duncan Wilson, Emma Hutley and Andy Johnston. Matt and Andy were due to ship out to Sierra Leone to assist in the medical response to Ebola, based in Kerrytown, so-called Operation GRITROCK. They were warm about the idea of piloting the system there and made a lot of helpful practical suggestions.

First though we had to demonstrate the system worked. Through Emma, we hooked up with Simon Weller and colleagues Jamie Taylor and Phil Rachwal at Dstl Porton Down. Dstl had access to archived Mayinga strain Ebola RNA material we could test the approach on.

We tried two methods initially - a direct metagenomics approach, spiking in Ebola RNA into mouse RNA to attempt direct detection. We were optimistic this might work because viral titres can be very high in Ebola. But this was actually a dismal failure in our hands.

Dan Turner from ONT came down to help us out and we eventually figured that a tiling PCR approach would give the best chance of success. Our first attempt at making a tiling scheme was overambitious - we assumed we would be able to generate very long fragments easily. But the material we were working with was old and quite degraded and we had virtually no amplification.

Slightly disheartened after two days of failure in the lab we returned to Birmingham to think about it again. This time we made a new tiling PCR scheme to generate 500 base amplicons, the 38 primer scheme referred to in the paper. Simon Weller at Dstl tried it out and it worked well. We were able to generate MinION sequence data - after persuading the company to give us an “offline” version - as we had no Internet access in the lab in Porton Down. We also sequenced the same pool on Illumina to act as validation.

Around the same time I was summoned to the Ministry of Defence to justify why our project should be approved by their ethics committee. It was quite exciting waiting in the grand Whitehall building. I think we waited for about 2 hours before we were called. And when we got in it was a quite daunting proposition with around 20 experts sitting around the table. Luckily I got off without a heavy grilling.

It seemed like the project might go ahead at this point in Kerrytown, and we sent the first batch of sequencing instruments and reagents out with Matt and Andy as part of the Gritrock deployment.

We then faced an agonising wait for ethical approval from the local Sierra Leone Ministry of Health. Understandable in the circumstances (I have waited for much longer for UK ethics committees to meet!), but frustrating, although we did eventually get approval. However, by then, it was far from clear how the work would be done as Matt and Andy had returned, and there was no obvious place in Kerrytown to do the work in, and no dedicated research team.

The project looked hopeless at this stage.

Around that time, in March, I had a chance meeting with Jon Green from PHE. He said that he knew of a colleague who was helping in Guinea who might be interested in trialling the system. His name was Miles Carroll and I realised quickly was notable for being the type of guy that just got stuff (shizz) done. Miles was working with the European Mobile Laboratories and Stephan Günther who had establishe an entire network of diagnostic laboratories in West Africa, testing over 10,000 samples during the epidemic. Miles had also previously sequenced 180 Ebola samples working with the University of Liverpool. He said “we’ve got the samples, we’ve got the ethics; you just need to get on a plane in 2 weeks time”.

Well - I’m not a lab guy - but I did think about going.

And I spoke to my other half.

And then I thought maybe Josh - both a lab person and a bioinformatician - would be a better person to go!

Well it wasn’t quite like that; he was enthusiastic but had to get permission from his girlfriend first. We had reassurances that he’d be staying in Guinea’s best “5*” hotel and would be under the protection of the WHO.

So he agreed!

Part 2: Prepz

Well, we knew kind of how we could sequence Ebola on the MinION at this point. But there was still a lot to be done.

Firstly Josh had to get his vaccinations - a whole heap of them in time for them to kick in. It took him days to find a willing GP who would give them at short notice.

Then we had to work out what to pack. This was very stressful. The timing was awful, I was laid up in bed with a brutal flu, and trying to coordinate with Josh at work through instant messenger (which he’s not very good at replying to at the best of times).

The worry was that with only a couple of weeks to do the work in, if we forgot anything we were dead meat. So Josh cleared down a small lab bench and started simulating MinION experiments to work out exactly what set of equipment he might need, bringing bits in.

I think it’s fair to say he nearly lost his mind doing this. There were issues about which equipment we could take, and how he would get it packed. He purchased a Pelican case from eBay for the fragile equipment.

We also didn’t have a thermocycler we could use, so we nicked my lab mate Damon Huber’s. Thanks Damon! You can have it back one day!

We also waited on WHO approval which we thought was all in hand, until the afternoon before leaving we received an email “MOST URGENT: !!!!!!!!!!!!! Re: No contract for Joshua Quick”. Turned out the documentation for his journey that was sent be email was bounced and was never received by WHO. He was due to fly at 6:55am!

He was up so late doing the final packing and repacking that I just went to sleep fully expecting to find out that Josh had missed his flight and the whole thing was off. But miraculously - at around noon - I heard he had made the flight and was on his way at it to Charles de Gaulle. The only hiccup is that Air France had charged him for excesss baggage.

“Don’t you realise this is a sequencing lab!?”

Merde!

Part 3: Doing the do

Josh hit the ground running and started with a test of amplicon sizes. He found he could mix and match primer pairs and was easily able to generate 1 kb amplicons from the fresh material he was working with and in fact tried sizes up to 6 kb with success, although the yields droppeddown as they got longer.

A bunch of recent samples were ready to be sequenced and he motored through them during his 2 weeks there.

The initial results looked great, with very high 2D pass rates. The big problem was uploading the data (we talk about this at length in the paper and the Supplement).

We started using a simple bioinformatics approach using the marginAlign software to call variants and started generating some rough phylogenetic trees, putting the data in context with previous data generated by Miles and his collaborators including Georgios Pollakis and Julian Hiscox from Liverpool and Dave Matthews in Bristol.

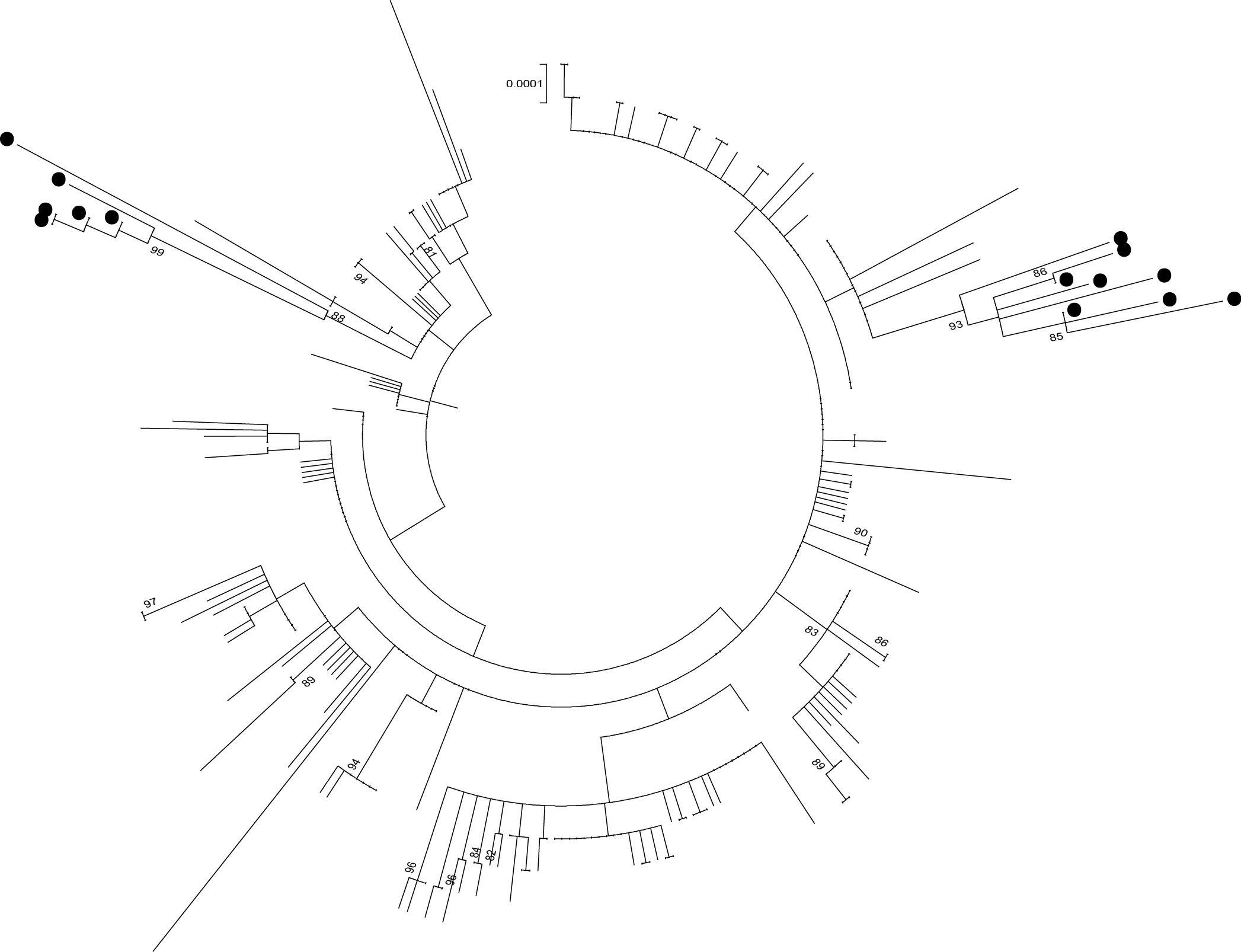

An early phylogeny from the MinION sequencing by Georgios Pollakis.

One of the first trees we generated was quite fascinating, demonstrating clear evidence of two - by now, given that the epidemic had been going for for around 18 months, quite distantly related lineages. The first lineage was named GN1 – and this had thought to have been made extinct by that point. As expected, there was a very long branch between our sequences and the previous ones from mid-2014. But without any other data to compare with, we could not see how the virus had spread from East to West Guinea. Later on more sequence data was released retrospectively and the gaps in the tree began to be filled in (you can see this for yourself at http://ebola.nextstrain.org)

Josh managed to get back safely - apart from a minor car crash involving the local gendarmerie - and after a quarantine period away from his girlfriend (at her request) returned home and got on with normal life.

As time went on we got more sophisticated with our tree building, bringing in various methods including BEAST, heavily assisted by Andrew Rambaut and Gytis Dudas in Edinburgh.

Andrew was very supportive of the project from the start and I remember an email from him saying “You mean to say some of these sequences were generated within 7 days of being taken? This is truly impressive!”

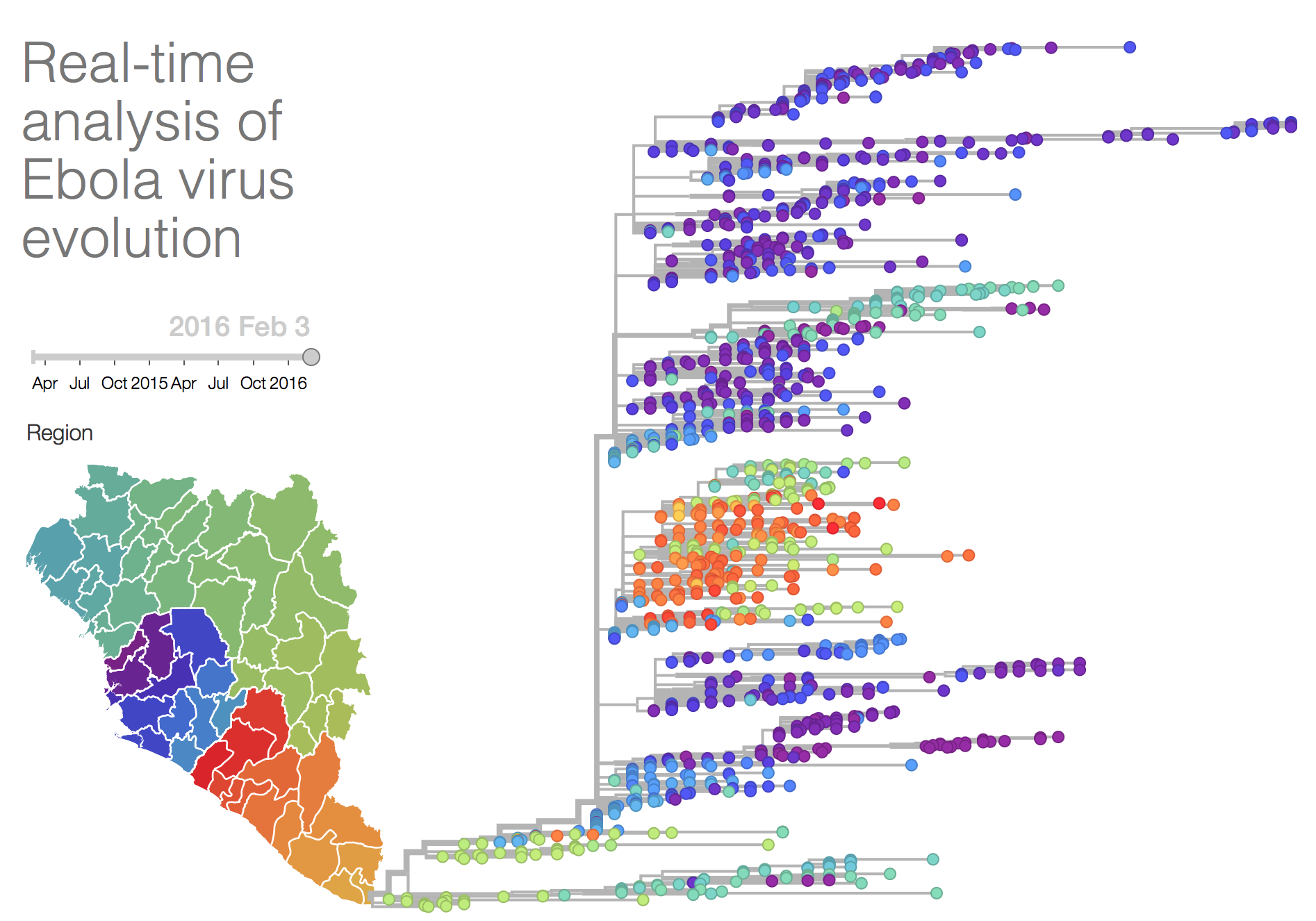

Andrew invited me to a meeting at Institut Pasteur to present. One awesome thing that happened there was being introduced to Richard Neher from the Max Planck by Andrew Rambaut at a viral genomics meeting in Paris. They had a PC set up demonstrating Nextflu.org which I was dimly aware of before, but realised this was exactly what was needed for Ebola.

Well they did not need this suggesting twice and with Trevor Bedford, Richard knocked up a version for Ebola which is accessible at http://ebola.nextstrain.org.

They kept (and keep) this updated for the outbreak with new sequences as they are released. It is awesome, go and check it out.

Over time we refined the analysis technique. We continued a very productive collaboration with Jared Simpson and moved to a signal-level analysis method that was able to generate very precise sequences, even from noisy nanopore data. For more information about this method, hop over to Jared’s blog.

We became more confident that the sequences we were generating were high quality and useful by reference to known chains of transmission and other datasets and root-to-tip regressions. Around this time Sophie Duraffour, who had helped Josh get setup, took over the sequencing. Presentations on our initial findings were made to the National Coordination and World Health Organisation and we were asked to make the sequencing a routine part of the outbreak response. It was interesting to see some epidemiologists really getting addicted to the genome data in the course of their investigations.

The work wasn’t all plain sailing for Sophie, she was involved in a terrifying armed robbery at a local hotel in Coyah.

But this event didn’t seem to affect her resolve and she has been working out with the European Mobile Laboratories for the majority of the outbreak now.

We moved the sequencer to a dedicated hut near the EMLab diagnostic unit in Coyah, in a rural part of Guinea east of Conakry. From there, Sophie spent a lot of time persuading other diagnostic outfits to send us leftover RNA to sequence.

We spent time liaising with epidemiologists such as Pierre Formenty, Ettore Severi and Amy Mikhail, trying to devise reports that they found informative and trying to make the bioinformatics analysis as quick as possible, building lots of pipelines.

One reporting format that was particularly popular was David Aanensen’s Microreact website which he and his team kindly added some features to specifically to help our project. The epidemiologists liked the output from that a great deal.

Over time, new people got trained to do the MinION sequencing, with oversight from Sophie. Lauren Cowley from Public Health England went out for a month’s stint - her slides from Genome Science 2015 show some of the creepy-crawlies that interfered with her library preparations. Unlike Josh’s visit, there was no hot running water in Coyah, so it was significantly less luxurious.

Two local Guinean researchers, Joseph Bore and Raymond Koundouno were trained on the system and continue to run the instrument to this day. Liana Kafetzopoulou, a new PhD student also got a turn. As can be seen from the author list on the paper, it was a huge team effort.

Photo by Tommy Trenchard (c) European Mobile Laboratories

Photo by Tommy Trenchard (c) European Mobile Laboratories

Another group doing amazing stuff was Ian Goodfellow’s, working with Matt Cotten and Paul Kellam at the Sanger Institute. They had managed the epic achievement of deploying an Ion Torrent PGM from a standing start into a lab in Sierra Leone. Whilst not as portable as our setup, I know from conversations that they put an immense effort into this work and generated many hundreds of genome sequences during their efforts. By putting the data together we detected several cross-border transmissions between Forecariah in Guinea and Kambia in Sierra Leone that we wouldn’t have otherwise seen, that we were able to notify the WHO about.

A great boon to this work was Andrew Rambaut’s http://www.virological.org which features a public and a private forum for us to discuss cases and interesting biology. Zika researchers are starting to use it right now.

Part 4: The Future

I think this project is part of a bigger shift for the practice of pathogen surveillance and epidemiology. We wrote about it in a piece for Genome Biology.

Photo by Tommy Trenchard (c) European Mobile Laboratories

Photo by Tommy Trenchard (c) European Mobile Laboratories

I think we stand now at a confluence of new technologies and ideas that are changing the way we can do epidemiology and public health surveillance, a discipline significantly hampered by lack of data.

Along with new portable technologies like nanopore, which we think will be transformative, and we have a new generation of researchers and epidemiologists who relish generating, interpreting and sharing genome data.

However, we still have social and political barriers to break down. The WHO put much effort into stating the importance of sharing of data. With Zika now being in the news there is another opportunity to “do it right” - share early, share often, or to get it wrong again. Hopefully we in the community will do it better this time.

This was probably one of the toughest, most fraught, most serious - but ultimately, also most satisfying projects I’vebeen involved with. It is a strange thing to say, in the context of such an awful, lethal epidemic. But I hope that research like this will impact future outbreak responses, hopefully by giving us tools to recognise and control such things way before they get out of control.